A Lifelong Scruff

By Peter Hitchens

Originally published in Valet Issue 1

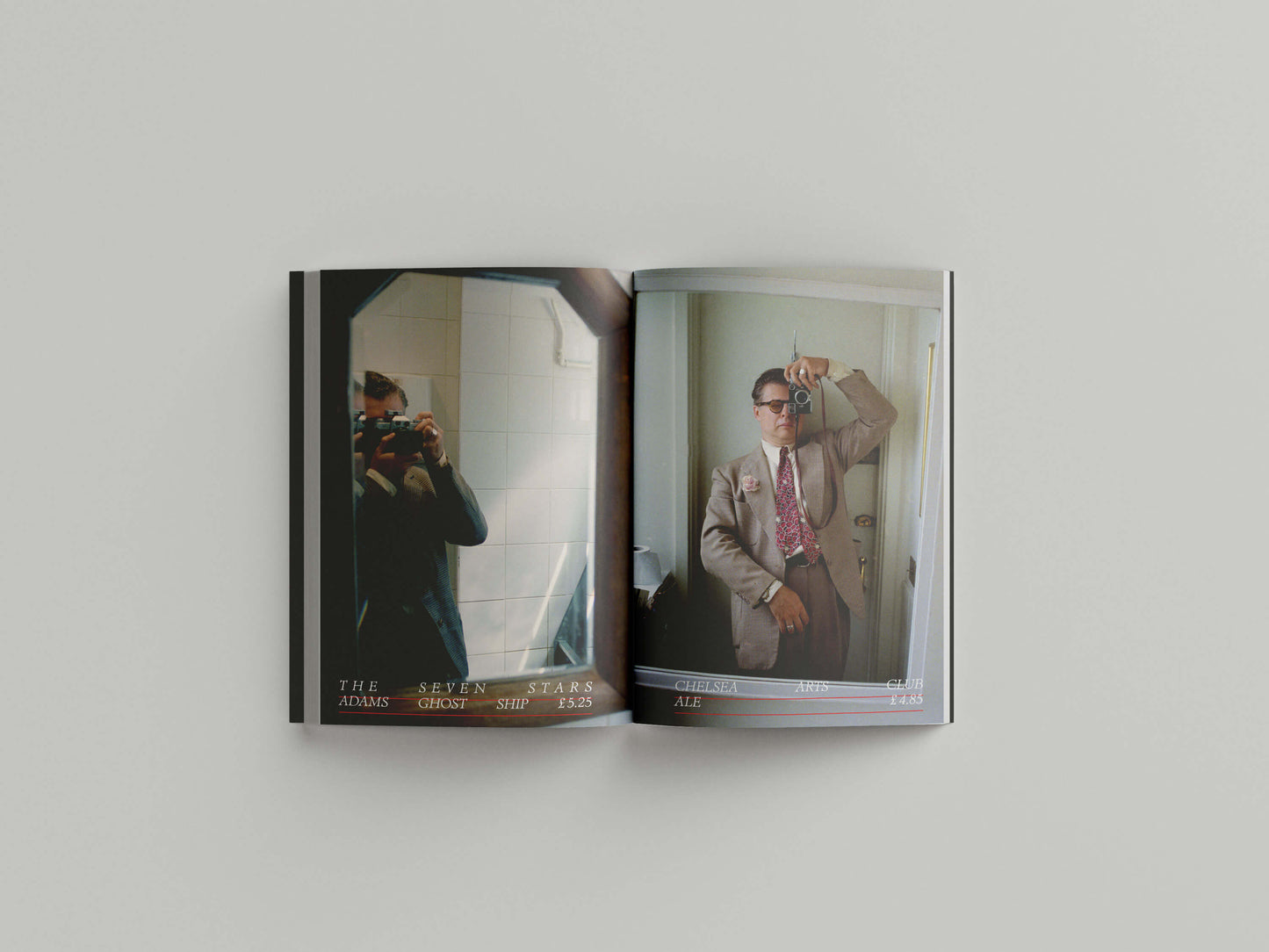

Robbie Burns has got his wish. In the modern world, it is almost impossible to avoid discovering how others see you, and what you look like to your enemies. I barely go a day without a rich crop of insults—mostly unoriginal and unamusing, but even so a useful corrective to any vanity or complacency. It has been interesting to see how much of this invective—usually from young, left-wing people who profess to hate all discrimination—includes the word ‘old’ (I am 68) in the list of things that are wrong with me. I usually respond by saying that I hope they will be lucky enough to one day become as old as I am now. Recently, however, as part of an outbreak of rage over an inconvenient news story I had written, I attracted the very personal ire of a furious, rather bilious (young) man on Twitter who had previously exhausted his spite by calling me a ‘racist’. This time, he rounded off a long list of my alleged faults by remarking that I dressed as if I had been startled from sleep by a fire alarm.

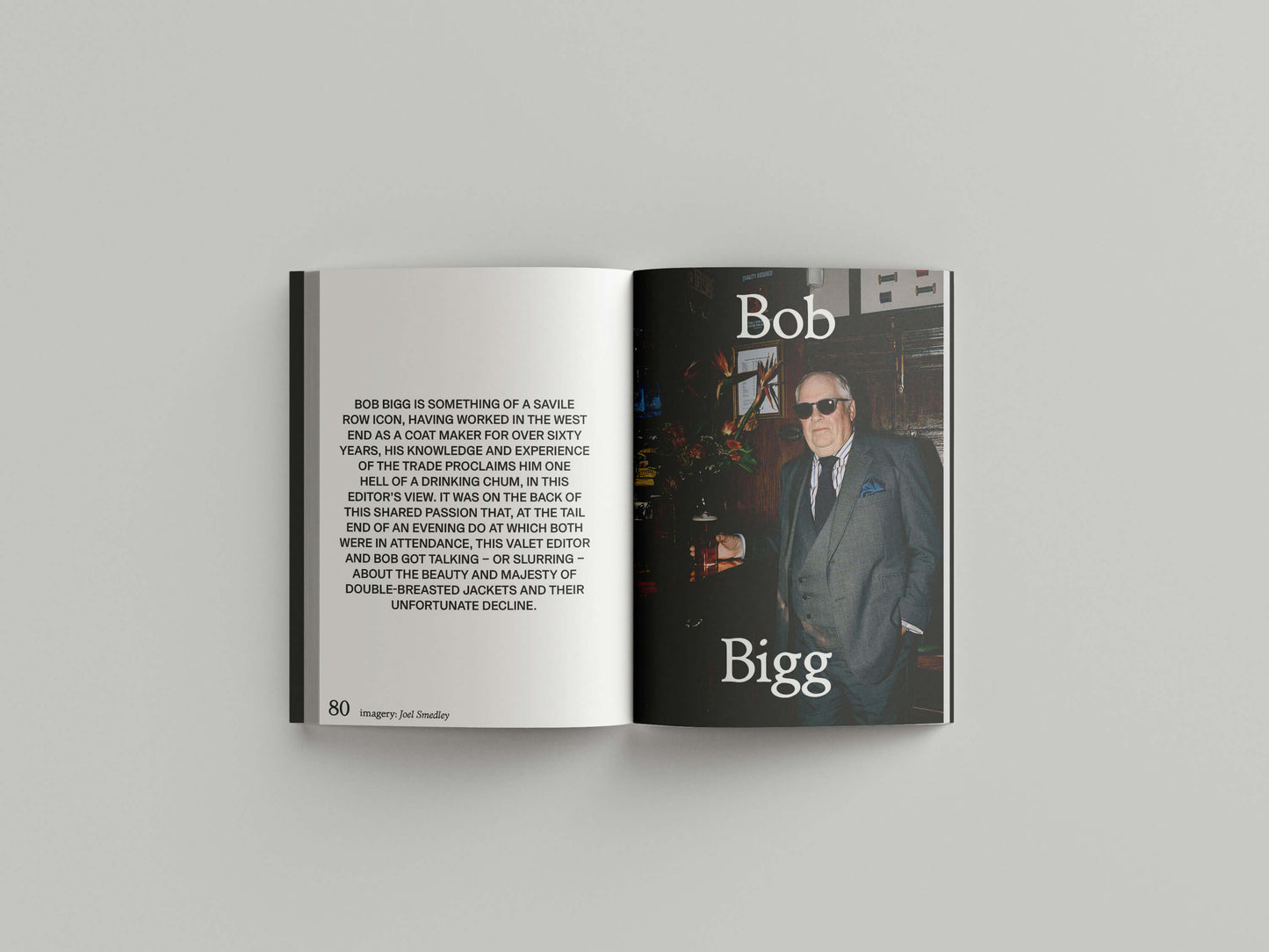

This made me laugh, because it is not entirely untrue. On occasion, I struggle into a suit that more or less fits me, though as I grow older and stouter, this becomes more of a problem. Descended as I am from squat peasants (some of my ancestors bear the fine and solid English name of Snuggs) and even squatter Cornish wreckers, I do not possess the classical proportions that the chain store designers assume when they decide how to allocate the measurements of their mass-produced trousers and jackets. And, as I would rather spend my money on practically anything other than clothes, I have to cope with this problem quite a lot, meaning that there is always a clash between theory and reality when I the time comes to purchase an off-the-peg outfit. Personally, I suspect that even the master tailors of Savile Row would blench, if confronted with my sturdy, strongly-built proportions; they would not want their labels to be observed on my person, for the sake of business. I seem to have the same special magic possessed by the great American lawyer Clarence Darrow, who complained that his suits quickly looked as if he had slept in them, even when he hadn’t.

But, you will say, that is just an excuse; that no doubt with a bit of effort and spending, I could overcome some of the problem; and I suppose it could. But I won’t do so, for I actively dislike sartorial smartness.

I am not sure exactly why. Is it generational? My father’s working gear, in my childhood, was a naval uniform. Actually, naval officers seldom look particularly tailored—I have never yet seen one (apart, perhaps, from that Olympically vain peacock, Earl Mountbatten, in full fig) whose jacket actually fits properly; it is the gold braid and rakish cap that give the outfit its charm and impact. And perhaps, if I had become (as I longed to in those days) a Destroyer captain, commanding and dangerous, I might have earned the right to wear these things. But I didn’t, and I have always thought the civilian male attire of our era to be among the dullest and least prepossessing apparel in all the ages of man. When others remark about how beautifully tailored such and such a celebrity is, I pretend to agree, but I genuinely cannot see what could possibly be beautiful about this odd ensemble.

Is it just upbringing? Many of my schooldays were spent in a reasonably enlightened boarding establishment, probably influenced by the example of Skipper Lynam’s Dragon School in Oxford. My headmaster might get into wild totalitarian rages about delinquents leaving their football kit on the changing room floor—a crime that sometimes led to terrible scenes and harsh collective punishments in breach of the Geneva Conventions—but he did not think there was any point in trying to get small boys to dress smartly. We were only required to attempt to be well-turned-out on Sunday mornings, and after Church was over, it was back into our normal garb, corduroy shorts and jumpers in winter and Aertex shirts in summer.

Our clothes had been sensibly chosen to be as wearable in the surrounding woodlands or moorland, or in rough playground games, as they were in the classroom. I can’t even remember what I did when I needed to wear non-uniform clothes in the holidays. I suspect that I often wore my school clothes because I was used to them, and at any rate, they didn’t look much like a uniform; even then, I simply I wasn’t interested. Children’s clothes of the time were generally durable and miniature versions of adult wear, but as to what I wore as I bicycled over the South Downs or roamed the suburbs of Portsmouth, I have no idea at all. I would make a terrible witness in a trial because, if asked what anyone was wearing at the scene of the crime, I would draw a complete blank. The very sight of a clothes shop has always filled me with boredom, and I enter them only out of necessity. I am quite taken with the policy of the fictional tough-guy Jack Reacher in Lee Child’s novels, who buys cheap clothes and then throws them away when they get dirty.

It was only when I went on to a minor public school, where I endured the early pangs of adolescence, that I was required to attempt smartness. It did not appeal. We were compelled to wear peculiar tweed jackets, known mysteriously as ‘sports jackets,’ which made the smaller boys resemble miniature bookmakers. The only other permitted choice was to don badged blazers, which made us look like tiny pub bores. For excursions into the nearby town, we were obliged to wear ridiculous caps—archaic even 50 years ago—presumably to make identification and detection easier if we got up to no good. And, there was the usual strange obsession of authority with our hair, which was particularly irksome in the middle 1960s, when the outside world was growing its locks, while we were incessantly told that we were not allowed to do so.

I had been passively uninterested in clothes all my life, and the silly pestering that I endured at this school hardened my indifference into active hostility. A few times in my life, I have been secretly horrified when people have (as has occasionally happened) paid me compliments on my dress sense. I continue to think it rude to pass remarks about how another man looks; I don’t regard it as my business, and I expect (or hope for) the same. Somebody once called me ‘dapper’ on a day when I arrived at work in a new suit, and I was so mortified that I was careful thereafter to distress any new clothes before appearing in them in public.

How happy I was to escape from school and spend my revolutionary years in jeans and reefer jackets. Later, working life later required me to attempt adult uniformity, but journalism has never—thank heaven—been a dressy trade and, as my enemy’s tweet pointed out, I don’t seek to make a snappy impression. During my years as a Moscow correspondent, when a new suit—in fact, almost any new garment—necessitated a 1,600-mile trip home, I let things go so much that Mikhail Gorbachev once canvassed me for my vote on a Moscow street, mistaking me for a particularly downtrodden Soviet citizen. I think that at that point, even I recognised that I might have let things slip too far, but to this day, I cling to the view that an English gentleman would rather be shabby than smart. To someone of my generation and background, there’ll always be something a bit untrustworthy about a chap with everything in place, who shoots his cuffs and buttons himself up tightly.

Valet subscription